Today, I visited the church where Charles H. Carrel, the subject of Saturday's post, is buried. I took photos of his grave and the church and added them to the account.

To illustrate the power of the Internet, it took me about four hours from the time I purchased Carrel's Bible on Saturday afternoon to piece together his biography using the inscriptions in the Bible as clues. I discovered where he was from, the basic details of his military service and death in the Civil War and the place where he is buried, which is just a 50 minutes' drive from my house.

At the cemetery, I learned the names of at least two of his siblings and the names of his parents and an aunt and uncle, and some basic genealogical information on the family.

By Saturday night, Carrel's story was on my blog.

Without the Internet, searching for these records would have taken several weeks at the very least. I think Mr. Charles H. Carrel would be pleased and amazed.

Sunday, June 25, 2006

Saturday, June 24, 2006

Dulce et decorum est ...

Charles H. Carrel (also spelled Carrell) received this Bible as a 21st birthday gift from his mother on June 19, 1860 -- 146 years ago this week.

On that day and on June 24, 1860 -- 146 years ago today -- he signed his name in a strong, proud, clear hand on the front and rear endpapers.

He didn't sign just plain Charles. He was Mr. Charles.

He was a stalwart son of North Jersey from Center Grove in Randolph Township near Morristown, Morris County. Center Grove is no longer a town, but rather a section of the township.

In the spring of 1861, Carrel was caught up in the wave of patriotism that washed over the Union following the Confederate bombardment in April of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina.

The Civil War was under way.

On May 27, 1861, he enlisted as a corporal in Co. B, 2nd N.J. Volunteer Infantry and trained with the regiment at a place called Camp Olden in Trenton.

On June 28, 1861 -- Wednesday will be the 145th anniversary -- the regiment left New Jersey for Virginia, 1,044 officers and men strong.

This Bible -- an inch and three-quarters thick, 5 inches long, three and a quarter inches wide -- was likely nestled in a corner of his knapsack.

Carrel must've been a good soldier. On Sept. 2, 1861, he was promoted to sergeant.

His regiment's first taste of combat was a series of battles called the Peninsula Campaign in Virginia in the spring and summer of 1862. The campaign was an unsuccessful attempt to capture the Confederate capital, Richmond.

On July 30, 1862, Carrel, just 23 years old, died of typhoid in a military hospital at Point Lookout, Md. He probably drank some bad water and was treated by a well-intentioned doctor who, like his colleagues, knew little about disease and even less about its spread.

A friend or relative marked Carrel's passing on a blank page in the Bible opposite the first page of the New Testament.

"He Died for his Country," reads the inscription.

He was buried in Mt. Freedom Presbyterian Cemetery, Randolph Township.

The inscription reads: "Chas H Carrell died July 30th 1862 At Point Lookout MD Aged 23 years ... He Died for his Country... The Lord gave + the Lord takeeth [sic] away blessed be the name of the Lord - Job Chap 21 verse - It is the Lord Let Him do what What [sic] seemeth Him good / Sam 3:18"

The inscription reads: "Chas H Carrell died July 30th 1862 At Point Lookout MD Aged 23 years ... He Died for his Country... The Lord gave + the Lord takeeth [sic] away blessed be the name of the Lord - Job Chap 21 verse - It is the Lord Let Him do what What [sic] seemeth Him good / Sam 3:18"By war's end in 1865, more than 600,000 men and boys on both sides had died, two-thirds of them, like Carrel, of disease.

This Bible rescues this young man from the realms of statistics and anonymity.

He was flesh and blood.

And the circle continues.

Charles Carrel's headstone

Charles Carrel's headstone The grave marker placed by the Grand Army of the Republic, an organization made up of Civil War veterans. Note that Carrel's name is misspelled.

The grave marker placed by the Grand Army of the Republic, an organization made up of Civil War veterans. Note that Carrel's name is misspelled. Footstone of Carrel's grave

Footstone of Carrel's grave

Wednesday, June 21, 2006

What are you reading?

What's on your summer reading list? Any books you care to recommend?

I just finished reading "Dispatches" by Michael Herr. Herr was a Vietnam War correspondent for Esquire magazine. His reminiscences, in the form of vignettes from the front lines, take me as close to being under fire as I care to get. Herr elicits compassion for the soldiers on both sides -- and especially for the Vietnamese civilians caught in the middle. He also imparts a clearer understanding of the truth that there really are no winners in war. At least that's what I got out of the book.

So, what are you reading?

I just finished reading "Dispatches" by Michael Herr. Herr was a Vietnam War correspondent for Esquire magazine. His reminiscences, in the form of vignettes from the front lines, take me as close to being under fire as I care to get. Herr elicits compassion for the soldiers on both sides -- and especially for the Vietnamese civilians caught in the middle. He also imparts a clearer understanding of the truth that there really are no winners in war. At least that's what I got out of the book.

So, what are you reading?

Tuesday, June 13, 2006

Dueling bridges

On Sunday, I had dinner with a former student from my years teaching English in Japan. She arrived in the States in late April and is living in Manhattan for a year while she studies at a language school downtown.

On the way to meet her, I took advantage of the beautiful weather to walk to the southernmost part of Manhattan, the oldest part of the city.

I hadn't been down there in a few years.

I had forgotten how gracefully and elegantly the Brooklyn Bridge and the Manhattan Bridge compete for the viewer's attention.

I was happy to see the rivalry going strong.

The Brooklyn Bridge is the people's bridge, the sightseer's bridge, the choice of cyclists and pedestrians year round.

The Manhattan Bridge is the forgotten stepchild, the thinker's bridge, the purposeful walker's bridge, the bridge famed more for the views it offers of its iconic neighbor.

And in the dead of winter when chill winds roil the East River, it's the lonely bridge you walk across if you want to feel you're the last person in creation.

Thursday, June 08, 2006

... and widens

The woman I mentioned in yesterday's post is Josephine Stockton (born Phin Thi Hang). Here's a link to her Web site.

And another circle begins ...

I got another call from Frank on Wednesday evening.

When we spoke Tuesday, I told him that I wanted to write about our unusual bond on my blog, and that his anonymity would be protected.

He was calling Wednesday to make a request.

"I want you to put in my real name," Frank said, "and also that I'm living in a home for veterans with PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] and drug and alcohol problems. If anyone else can be helped by this, I want to do it.

"The home does a great job, and they can use the plug."

So for the record, his name is Claude Frank Wright Jr., and he goes by Claude. He lives in the C.O.P.I.N. Foundation home in Niagara Falls, N.Y.

Claude said his Purple Heart medal went missing during the course of one of his many moves. He thinks it may have been stolen.

"I noticed it was missing several years ago," he said. "I personally think it was stolen because I keep all my stuff together. I had it all stored in one place. I've been missing it so long.

"You don't know how thrilled I am to get this back."

About an hour after talking with Claude, I got an e-mail from a woman who read about my efforts to return his medal to him on a Web site where I posted a request for information from anyone who may have known him.

The woman didn't know Claude but was interested in his experiences because they related to her own. She said she fled Saigon on the last American C-130 cargo plane to leave the South Vietnamese capital before it fell in April 1975. She said she met a lot of U.S. soldiers while living in Saigon and also during humanitarian visits she has made back to Vietnam in the ensuing years.

OK, I thought, this woman was probably a military nurse, or maybe a civilian employee on a military base.

She signed her name, an ordinary Western name about which you wouldn't think twice.

She also included a link to her Web site.

On that site, I learned that the name she affixed to her e-mail was an anglicization of her Vietnamese name. In Saigon during the war, she worked as a bar girl. She is ethnically Cambodian and was subjected to severe racism in Vietnam. She eventually married an American and is now living in the United States.

If she gives me permission, I'll provide her Web site address in another post.

I told Claude, and I told this woman, that I believe that nothing in our lives happens at random. I think everything is interrelated and I don't think there's necessarily anything cosmic or freaky or weird or ironic or scary or inexplicable about it.

It just is.

I don't think it's a Buddhist thing or a Christian, Jewish, Islamic or Hindu thing. It's all about being part of the same fabric.

There's a reason why I bought that Purple Heart medal on eBay, which led to my meeting a bunch of Vietnam vets who encouraged me in my quest to return it to its owner, which led to my meeting Claude, which led to my meeting that woman.

If you don't think we're all in the same boat and that our lives don't intersect somehow, some way, then have I got a story for you.

When we spoke Tuesday, I told him that I wanted to write about our unusual bond on my blog, and that his anonymity would be protected.

He was calling Wednesday to make a request.

"I want you to put in my real name," Frank said, "and also that I'm living in a home for veterans with PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] and drug and alcohol problems. If anyone else can be helped by this, I want to do it.

"The home does a great job, and they can use the plug."

So for the record, his name is Claude Frank Wright Jr., and he goes by Claude. He lives in the C.O.P.I.N. Foundation home in Niagara Falls, N.Y.

Claude said his Purple Heart medal went missing during the course of one of his many moves. He thinks it may have been stolen.

"I noticed it was missing several years ago," he said. "I personally think it was stolen because I keep all my stuff together. I had it all stored in one place. I've been missing it so long.

"You don't know how thrilled I am to get this back."

About an hour after talking with Claude, I got an e-mail from a woman who read about my efforts to return his medal to him on a Web site where I posted a request for information from anyone who may have known him.

The woman didn't know Claude but was interested in his experiences because they related to her own. She said she fled Saigon on the last American C-130 cargo plane to leave the South Vietnamese capital before it fell in April 1975. She said she met a lot of U.S. soldiers while living in Saigon and also during humanitarian visits she has made back to Vietnam in the ensuing years.

OK, I thought, this woman was probably a military nurse, or maybe a civilian employee on a military base.

She signed her name, an ordinary Western name about which you wouldn't think twice.

She also included a link to her Web site.

On that site, I learned that the name she affixed to her e-mail was an anglicization of her Vietnamese name. In Saigon during the war, she worked as a bar girl. She is ethnically Cambodian and was subjected to severe racism in Vietnam. She eventually married an American and is now living in the United States.

If she gives me permission, I'll provide her Web site address in another post.

I told Claude, and I told this woman, that I believe that nothing in our lives happens at random. I think everything is interrelated and I don't think there's necessarily anything cosmic or freaky or weird or ironic or scary or inexplicable about it.

It just is.

I don't think it's a Buddhist thing or a Christian, Jewish, Islamic or Hindu thing. It's all about being part of the same fabric.

There's a reason why I bought that Purple Heart medal on eBay, which led to my meeting a bunch of Vietnam vets who encouraged me in my quest to return it to its owner, which led to my meeting Claude, which led to my meeting that woman.

If you don't think we're all in the same boat and that our lives don't intersect somehow, some way, then have I got a story for you.

Wednesday, June 07, 2006

Sacrifice comes full circle

My cellphone rang at about 6 on Tuesday evening.

"May I speak with Michael," asked a raspy, unfamiliar voice.

"Speaking," I said.

"Hello, my friend. You sent me a letter last week trying to get in contact with me."

It was Frank, the Marine Corps veteran of Vietnam whose Purple Heart medal I bought at online auction last year.

He was calling me from a veterans home in upstate New York.

My heart skipped a beat.

This was the man, the complete stranger, to whom I needed to return what rightfully was his.

Frank said he lost the medal three years ago. I didn't ask how. I figured it was none of my business. I thought that asking about its loss might somehow imply doubt on my part. Anyway, it wasn't important.

He wanted to know how I found him. I explained how I searched a public records database at work and came up with a name that I hoped would be the right one. And then I sent a letter to the address exactly one week ago.

"Just a stab in the dark," he said.

He asked me how I acquired his medal. I told him about eBay.

"I didn't know they could sell medals on eBay," he said.

Unfortunately, they can. It seems that everything in our society, even recognition of valor and blood sacrifice, can be bought for the right price.

The paperwork that accompanies Frank's Purple Heart indicates the date it was bestowed, but not the circumstances. I wanted to know, and asked Frank if he would be uncomfortable in relating the story.

"You're not asking questions about blood and gore, so it's OK," he said.

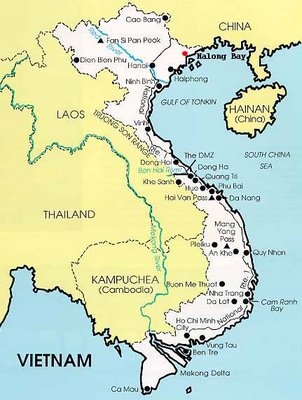

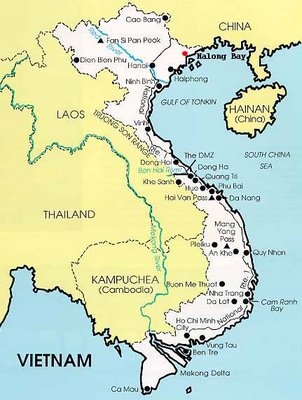

Frank was stationed in the village of Phu Bai on Highway 1 near Da Nang in April 1968. His Marine squad of about 15 men was living in the village on a one-year assignment, working side-by-side with the villagers in defending their homes against attack.

"I caught a Chicom grenade [manufactured in mainland China] and got shrapnel in my back," Frank said. "I was medevac'ed out and was in the hospital for a month."

I asked Frank what it was like living in that village.

"You had to be on your toes," he said. "We had a compound in front of the village. Then we got rid of that and moved into the village.

"At night we had to set ambushes. I don't trust anybody, I don't care who it is. You couldn't tell friend from enemy because everyone looked the same.

"You had to stay alert."

Frank was very glad that I had sent that letter. I told him how I had agonized over whether to try to find him, not knowing what wounds of his I might be reopening. He said he was grateful, and that I shouldn't worry.

I, too, am grateful. Grateful that I had the chance to close this circle.

"May I speak with Michael," asked a raspy, unfamiliar voice.

"Speaking," I said.

"Hello, my friend. You sent me a letter last week trying to get in contact with me."

It was Frank, the Marine Corps veteran of Vietnam whose Purple Heart medal I bought at online auction last year.

He was calling me from a veterans home in upstate New York.

My heart skipped a beat.

This was the man, the complete stranger, to whom I needed to return what rightfully was his.

Frank said he lost the medal three years ago. I didn't ask how. I figured it was none of my business. I thought that asking about its loss might somehow imply doubt on my part. Anyway, it wasn't important.

He wanted to know how I found him. I explained how I searched a public records database at work and came up with a name that I hoped would be the right one. And then I sent a letter to the address exactly one week ago.

"Just a stab in the dark," he said.

He asked me how I acquired his medal. I told him about eBay.

"I didn't know they could sell medals on eBay," he said.

Unfortunately, they can. It seems that everything in our society, even recognition of valor and blood sacrifice, can be bought for the right price.

The paperwork that accompanies Frank's Purple Heart indicates the date it was bestowed, but not the circumstances. I wanted to know, and asked Frank if he would be uncomfortable in relating the story.

"You're not asking questions about blood and gore, so it's OK," he said.

Frank was stationed in the village of Phu Bai on Highway 1 near Da Nang in April 1968. His Marine squad of about 15 men was living in the village on a one-year assignment, working side-by-side with the villagers in defending their homes against attack.

"I caught a Chicom grenade [manufactured in mainland China] and got shrapnel in my back," Frank said. "I was medevac'ed out and was in the hospital for a month."

I asked Frank what it was like living in that village.

"You had to be on your toes," he said. "We had a compound in front of the village. Then we got rid of that and moved into the village.

"At night we had to set ambushes. I don't trust anybody, I don't care who it is. You couldn't tell friend from enemy because everyone looked the same.

"You had to stay alert."

Frank was very glad that I had sent that letter. I told him how I had agonized over whether to try to find him, not knowing what wounds of his I might be reopening. He said he was grateful, and that I shouldn't worry.

I, too, am grateful. Grateful that I had the chance to close this circle.

Tuesday, June 06, 2006

Health update

I learned following my blood test last month that my serum calcium level had risen. My endocrinologist increased my medication accordingly. I'm now taking the maximum dose of four pills per day.

On Thursday, I'm scheduled for another blood test to see if my calcium level has responded. Physically, I'm feeling better than before the dosage was increased, so I suspect that the level has dropped.

Nonetheless, I would be obliged if you would continue to keep me in your thoughts and prayers. This isn't a single battle that needs to be won. It's a campaign.

On Thursday, I'm scheduled for another blood test to see if my calcium level has responded. Physically, I'm feeling better than before the dosage was increased, so I suspect that the level has dropped.

Nonetheless, I would be obliged if you would continue to keep me in your thoughts and prayers. This isn't a single battle that needs to be won. It's a campaign.

Thursday, June 01, 2006

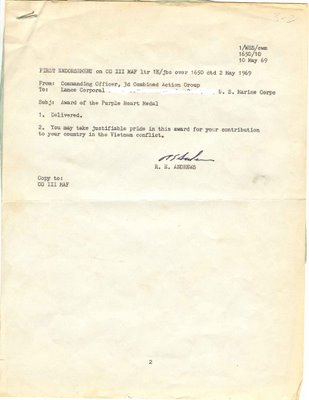

"You may take justifiable pride ..."

I'm fascinated by the Vietnam War.

I grew up amid its demonstrations and rallies, its headlines and TV coverage.

I remember the dinnertable debates between my dad, a veteran of World War II, and my brother, who was of prime draft age. I remember my mother's worry, even though I was too young to comprehend it fully.

And so when I saw an identified Purple Heart medal from Vietnam at auction online about a year ago, I placed a bid without hesitation.

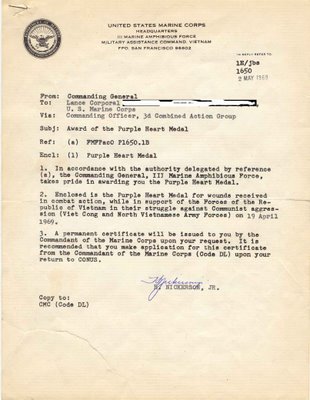

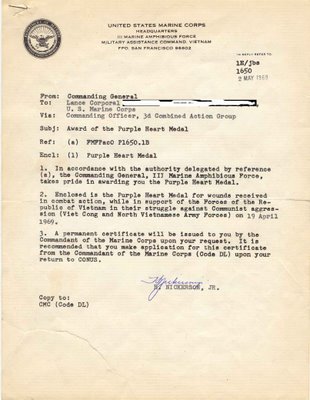

It had been presented to a Marine lance corporal in the 3rd Marine Amphibious Force, 3rd Combined Action Group. He was wounded in April 1969 -- around the time of his 20th birthday, I later found out. With it came the original paperwork that accompanied the medal, advising this soldier (I'll call him "Frank" to protect his identity) that he "may take justifiable pride in this award for your contribution to your country in the Vietnam conflict" for wounds received in the "struggle against Communist aggression."

The man who sold it to me offered no provenance other than that it was bought at a garage sale near Buffalo, N.Y. I did some fruitless preliminary research on Frank and put the project aside.

On Memorial Day, my thoughts returned to the Purple Heart that I had tucked away in my book cabinet.

On Memorial Day, my thoughts returned to the Purple Heart that I had tucked away in my book cabinet.

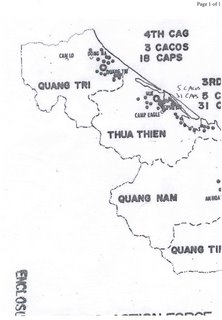

I did a Google search of Frank's unit, just as it appeared on his citation: "III Marine Amphibious Force, 3rd Combined Action Group." I got just two matches.

Meanwhile, I found a Web site put together by a man who collects Purple Hearts. I asked him how to go about researching the recipient. He told me to request copies of Frank's military records from the National Archives, but warned that the amount of information released is quite limited due to privacy concerns.

He also suggested researching Frank's unit on the Web. "Try Googling '3rd Combined Action Group,' " he wrote in an e-mail.

That was the key. In my prior search, I had entered too much information. This time, I did Google searches on "3rd Combined Action Group" and "3rd Combined Action" and came up with more than 40 matches.

Frank's Purple Heart and Marine Corps cap and collar insignia. Based upon the serial number engraved on its edge, the medal is World War 2 surplus, a collector informed me. There were so many made during that war that the back stock was still being distributed through the Korean and Vietnam wars.

Frank's Purple Heart and Marine Corps cap and collar insignia. Based upon the serial number engraved on its edge, the medal is World War 2 surplus, a collector informed me. There were so many made during that war that the back stock was still being distributed through the Korean and Vietnam wars.

Among them was a Web site devoted to the Marine Corps' Combined Action Program, a lesser-known but fascinating chapter in the history of the war. The CAP, which ran from 1965-71, assigned squads of about 15 Marine riflemen plus a Navy corpsman to villages along the central coast in hotly contested territory. They were almost always led by a non-commissioned officer, usually a sergeant but sometimes a corporal. The men would live in these villages for a year, participating in all aspects of village life and helping to defend the inhabitants against enemy attack by fighting alongside local militia known as Popular Forces.

A Marine veteran of a CAP unit described the program on a Web site as "like the Peace Corps with guns."

These platoons were seen as an alternative to the prevailing "search and destroy" tactics then favored by the U.S. military, in that the squads didn't leave villages after clearing them of enemy forces. The program, intended to build goodwill with the Vietnamese, is viewed by historians and participants as one of the success stories of the war.

The Marines assigned only their best soldiers to the program. About 5,000 served in the CAP ranks during the six years of the program.

Casualties in the platoons were very high because the units served in isolated areas far from reinforcements. They were constantly on the move in the areas surrounding their villages. They were at the very front of the front lines.

The units' unofficial motto was "We're All Alone in Indian Country."

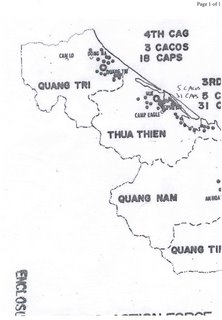

Frank served in one of the 3rd Combined Action Group's 31 platoons somewhere in Thua Thien province, near Hue and Phu Bai, about a hundred miles from the Demilitarized Zone that divided North and South Vietnam.

Now I wanted to learn more about Frank.

About a week ago, I checked a score of CAP- and Vietnam-veterans-related Web sites to see if he belonged to any veterans groups, and to inquire whether anyone had known him.

No luck so far.

Then I searched an online database of public records to which I have access at the newspaper where I work.

All I had were Frank's name (his surname is fairly common) and a general idea of where he came from, based on the account from the man who sold me the medal that he had acquired it near Buffalo, N.Y.

My search quickly narrowed to one man. The name was an identical match and his age (he was born in April 1949) was within the right range.

I discovered a man who had moved around a lot within the past dozen years. I checked all the addresses and phone numbers I found, all of them dead ends.

His last known address is a post office box.

I called the post office in that town and asked whether this man still maintained a box there.

"Sorry, can't give you that information," the clerk said. "Privacy rules."

I explained why I was searching for Frank.

"Wait a minute," the clerk said, putting me on hold. After a half-minute he was back on the line. "Look, all I can tell you is that if you were to address a letter to that man at that box number, he'll get it. Either he's picking up his mail or someone's picking it up for him."

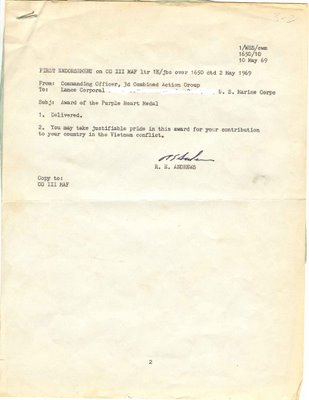

Paperwork that accompanied Frank's Purple Heart medal. His name and service number have been concealed to protect his identity.

Paperwork that accompanied Frank's Purple Heart medal. His name and service number have been concealed to protect his identity.

I spent an hour deliberating what to do.

I would love to give this medal back to Frank. A CAP Marine veteran with whom I've struck up a correspondence told me that few veterans would willingly part with something like a Purple Heart. The medal represents the literal giving of a piece of the self of the person upon whom it is bestowed.

It could be that the medal was sold by an ex-wife or girlfriend after an acrimonious divorce or breakup. Perhaps it was sold by one of Frank's kids. Maybe Frank sold it to exorcise the ghosts of his past. Or to raise badly needed money.

Maybe Frank died recently, his personal effects scattered to the four winds.

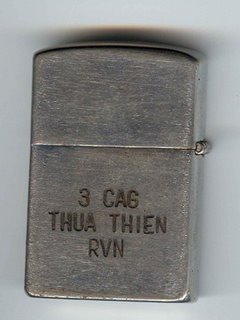

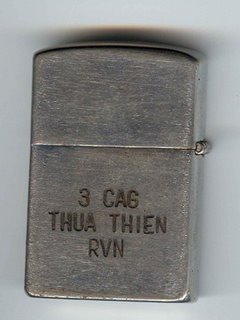

Souvenir lighter that belonged to a CAP Marine from the same unit as Frank: 3[rd] C[ombined] A[action] G[roup], THUA THIEN [province], R[epublic of] V[iet] N[am]

Souvenir lighter that belonged to a CAP Marine from the same unit as Frank: 3[rd] C[ombined] A[action] G[roup], THUA THIEN [province], R[epublic of] V[iet] N[am]

Would Frank be grateful that someone would take the trouble to return to him a possession fraught with so much emotional significance? Would he resent the intrusion, the awakening of sleeping dogs? Would he accept the medal only to sell it again?

Would my curiosity rip open old wounds and add to a man's misery?

Did I even have the right man?

I decided to write to Frank. I would apologize for the intrusion. I would detail how and why I located him. I would tell him of my great interest in learning more about what he saw, thought and felt during his time in Vietnam.

I would offer him my contact information, hope for the best and resolve to drop the issue forever if I didn't hear from him within a reasonable time.

That letter was mailed Tuesday.

I'll post any updates on my blog.

I grew up amid its demonstrations and rallies, its headlines and TV coverage.

I remember the dinnertable debates between my dad, a veteran of World War II, and my brother, who was of prime draft age. I remember my mother's worry, even though I was too young to comprehend it fully.

And so when I saw an identified Purple Heart medal from Vietnam at auction online about a year ago, I placed a bid without hesitation.

It had been presented to a Marine lance corporal in the 3rd Marine Amphibious Force, 3rd Combined Action Group. He was wounded in April 1969 -- around the time of his 20th birthday, I later found out. With it came the original paperwork that accompanied the medal, advising this soldier (I'll call him "Frank" to protect his identity) that he "may take justifiable pride in this award for your contribution to your country in the Vietnam conflict" for wounds received in the "struggle against Communist aggression."

The man who sold it to me offered no provenance other than that it was bought at a garage sale near Buffalo, N.Y. I did some fruitless preliminary research on Frank and put the project aside.

On Memorial Day, my thoughts returned to the Purple Heart that I had tucked away in my book cabinet.

On Memorial Day, my thoughts returned to the Purple Heart that I had tucked away in my book cabinet.I did a Google search of Frank's unit, just as it appeared on his citation: "III Marine Amphibious Force, 3rd Combined Action Group." I got just two matches.

Meanwhile, I found a Web site put together by a man who collects Purple Hearts. I asked him how to go about researching the recipient. He told me to request copies of Frank's military records from the National Archives, but warned that the amount of information released is quite limited due to privacy concerns.

He also suggested researching Frank's unit on the Web. "Try Googling '3rd Combined Action Group,' " he wrote in an e-mail.

That was the key. In my prior search, I had entered too much information. This time, I did Google searches on "3rd Combined Action Group" and "3rd Combined Action" and came up with more than 40 matches.

Frank's Purple Heart and Marine Corps cap and collar insignia. Based upon the serial number engraved on its edge, the medal is World War 2 surplus, a collector informed me. There were so many made during that war that the back stock was still being distributed through the Korean and Vietnam wars.

Frank's Purple Heart and Marine Corps cap and collar insignia. Based upon the serial number engraved on its edge, the medal is World War 2 surplus, a collector informed me. There were so many made during that war that the back stock was still being distributed through the Korean and Vietnam wars.Among them was a Web site devoted to the Marine Corps' Combined Action Program, a lesser-known but fascinating chapter in the history of the war. The CAP, which ran from 1965-71, assigned squads of about 15 Marine riflemen plus a Navy corpsman to villages along the central coast in hotly contested territory. They were almost always led by a non-commissioned officer, usually a sergeant but sometimes a corporal. The men would live in these villages for a year, participating in all aspects of village life and helping to defend the inhabitants against enemy attack by fighting alongside local militia known as Popular Forces.

A Marine veteran of a CAP unit described the program on a Web site as "like the Peace Corps with guns."

These platoons were seen as an alternative to the prevailing "search and destroy" tactics then favored by the U.S. military, in that the squads didn't leave villages after clearing them of enemy forces. The program, intended to build goodwill with the Vietnamese, is viewed by historians and participants as one of the success stories of the war.

The Marines assigned only their best soldiers to the program. About 5,000 served in the CAP ranks during the six years of the program.

Casualties in the platoons were very high because the units served in isolated areas far from reinforcements. They were constantly on the move in the areas surrounding their villages. They were at the very front of the front lines.

The units' unofficial motto was "We're All Alone in Indian Country."

Frank served in one of the 3rd Combined Action Group's 31 platoons somewhere in Thua Thien province, near Hue and Phu Bai, about a hundred miles from the Demilitarized Zone that divided North and South Vietnam.

Now I wanted to learn more about Frank.

About a week ago, I checked a score of CAP- and Vietnam-veterans-related Web sites to see if he belonged to any veterans groups, and to inquire whether anyone had known him.

No luck so far.

Then I searched an online database of public records to which I have access at the newspaper where I work.

All I had were Frank's name (his surname is fairly common) and a general idea of where he came from, based on the account from the man who sold me the medal that he had acquired it near Buffalo, N.Y.

My search quickly narrowed to one man. The name was an identical match and his age (he was born in April 1949) was within the right range.

I discovered a man who had moved around a lot within the past dozen years. I checked all the addresses and phone numbers I found, all of them dead ends.

His last known address is a post office box.

I called the post office in that town and asked whether this man still maintained a box there.

"Sorry, can't give you that information," the clerk said. "Privacy rules."

I explained why I was searching for Frank.

"Wait a minute," the clerk said, putting me on hold. After a half-minute he was back on the line. "Look, all I can tell you is that if you were to address a letter to that man at that box number, he'll get it. Either he's picking up his mail or someone's picking it up for him."

Paperwork that accompanied Frank's Purple Heart medal. His name and service number have been concealed to protect his identity.

Paperwork that accompanied Frank's Purple Heart medal. His name and service number have been concealed to protect his identity.I spent an hour deliberating what to do.

I would love to give this medal back to Frank. A CAP Marine veteran with whom I've struck up a correspondence told me that few veterans would willingly part with something like a Purple Heart. The medal represents the literal giving of a piece of the self of the person upon whom it is bestowed.

It could be that the medal was sold by an ex-wife or girlfriend after an acrimonious divorce or breakup. Perhaps it was sold by one of Frank's kids. Maybe Frank sold it to exorcise the ghosts of his past. Or to raise badly needed money.

Maybe Frank died recently, his personal effects scattered to the four winds.

Souvenir lighter that belonged to a CAP Marine from the same unit as Frank: 3[rd] C[ombined] A[action] G[roup], THUA THIEN [province], R[epublic of] V[iet] N[am]

Souvenir lighter that belonged to a CAP Marine from the same unit as Frank: 3[rd] C[ombined] A[action] G[roup], THUA THIEN [province], R[epublic of] V[iet] N[am]Would Frank be grateful that someone would take the trouble to return to him a possession fraught with so much emotional significance? Would he resent the intrusion, the awakening of sleeping dogs? Would he accept the medal only to sell it again?

Would my curiosity rip open old wounds and add to a man's misery?

Did I even have the right man?

I decided to write to Frank. I would apologize for the intrusion. I would detail how and why I located him. I would tell him of my great interest in learning more about what he saw, thought and felt during his time in Vietnam.

I would offer him my contact information, hope for the best and resolve to drop the issue forever if I didn't hear from him within a reasonable time.

That letter was mailed Tuesday.

I'll post any updates on my blog.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)